Reflections on ASCO 2023

The need for more Randomized Controlled Trials

Obligatory—This is not medical advice

These last few days, I had the ability to attend the American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting in Chicago.1 It’s an amazing experience, being able to spend time with colleagues and learn. I also use my downtime to reflect.

During the Q&A portion of the oral abstract session, which took place on Monday, June 5th, a senior sarcoma oncologist aptly summarized the state of trials in sarcoma. While I will attempt to paraphrase his words, it is important to acknowledge that my interpretation may not fully capture his message. This oncologist noted that our field has been highly productive in conducting single-arm and randomized phase II studies in sarcoma. However, due to the diverse endpoints and inclusion of various histologic subtypes, the resulting picture remains unclear. The landscape is littered with different combinations of TKIs, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy, making it challenging to interpret the implications of the data when there is no comparator, and the patient population is not well-defined. This is not to take away from the accomplishments of investigators, who continue to enroll to clinical trials which benefit patients. What we need now, however, for patients is a precise map to guide us. I worry that much of our recent data does not help cartographically (overuse of this metaphor, my apologies).

In the long run, what holds the most significance for patients is understanding the context in which each treatment fits. Randomized clinical trials conducted in melanoma, for example, have clarified that immunotherapy is superior to targeted treatments as a first-line therapy. Patients who were eligible for both treatments experienced longer survival when receiving immunotherapy before BRAF/MEK inhibition.2 This answered an important question and shaped the standard of care. Now, patients with melanoma, even with BRAF mutations, are typically administered immunotherapy, and they will live longer because of this.

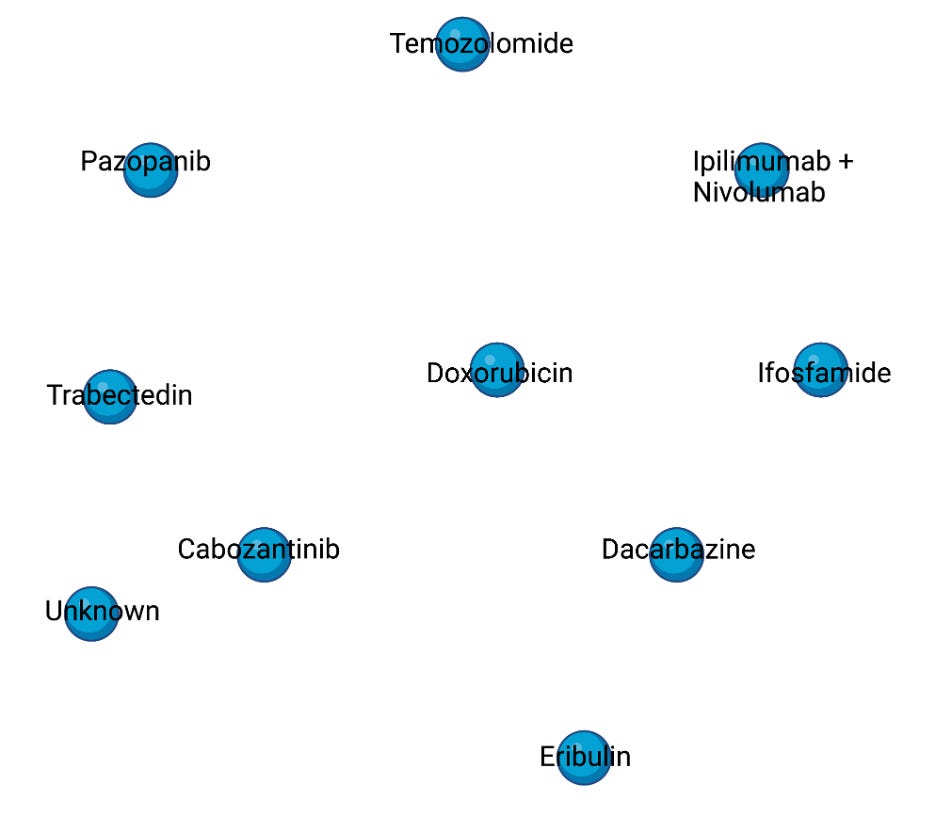

While this analogy may oversimplify the matter, determining the sequence of treatments for patients with cancer is much like answering a more probabilistic version of the traveling salesman problem. It signifies that with an increased number of potential therapies, we must empirically have measured the efficacy of each in relation to the others. Instead, and unfortunately, we have woven a complex web of disconnected points without a clear guide, leaving us unaware of their relative effectiveness. Consequently, we are faced with a multitude of treatment options but a lack of awareness regarding which one is most suitable for many patients.

The importance of randomized controlled trials cannot be overstated. In order to effectively serve our patients, it is crucial that we have a means to measure the impact of interventions. In future posts, I will delve further into how I believe we can feasibly accomplish this.

https://conferences.asco.org/am/attend

https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/JCO.22.01763