I’ve written previously about how I prepare for the first visit with a new patient. It’s somewhat of an inversion of the normal doctor visit paradigm and makes the encounter entirely patient directed. I report their history as it’s been document. I’ve been told that it establishes trust upfront. We then work together in order to build a suitable treatment plan. There are instances where we can deviate from this, certainly, but large and by this is the majority of my new patient visits. After I open up for questions, the first thing I’m asked is usually this: Do I need chemotherapy? It’s a reasonable one and the question preceding every visit, so I get it.

I try to define terms as best I can in my response. This is called symbolic grounding. It’s vital to really make sure that our communication is rooted in the same vernacular. I try to convey each chemotherapy in regards to how it might be used as a tool. What are its limitations and its potential benefits? How likely do we imagine a patient with their diagnosis is to respond to chemotherapy? This is what people care about. In the abstract, it’s all less certain, but when we dial in the meaning of these words, we can empower people to make their best decisions. There are not universal truths here, as we will explore.

What is or was the standard?

Again, I say we’re in an area of controversy. Within the sarcoma-sphere we rely on the data from randomized and other trials to guide us. I’ll reference some trials, and certainly not all. Firstly, we have our keystone trial, mentioned previously, published by Judson et al. which demonstrated no survival benefit for patients who received both ifosfamide and doxorubicin, as compared to those who received doxorubicin alone. 1 This was not a trial performed purely on patients with leiomyosarcoma. Patients with leiomyosarcoma composed approximately 25% of each group. The statistical methods employed did not have the capacity to measure leiomyosarcoma specifically with reasonable confidence. We talk about the general population of patients with soft tissue sarcoma.

To summarize, while a higher proportion of patients had response (meaning their tumors shrank >30% in sum of largest diameters), and a larger duration of time until their tumors grew again, the average patient did not live longer. Furthermore, the rate of toxicity was much higher numerically in the combination group. This has led most physicians to recommend doxorubicin, in lieu of doxorubicin and ifosfamide in situation where a response is not needed quickly. I’ve included the figure again for reference.

Gemcitabine and Docetaxel

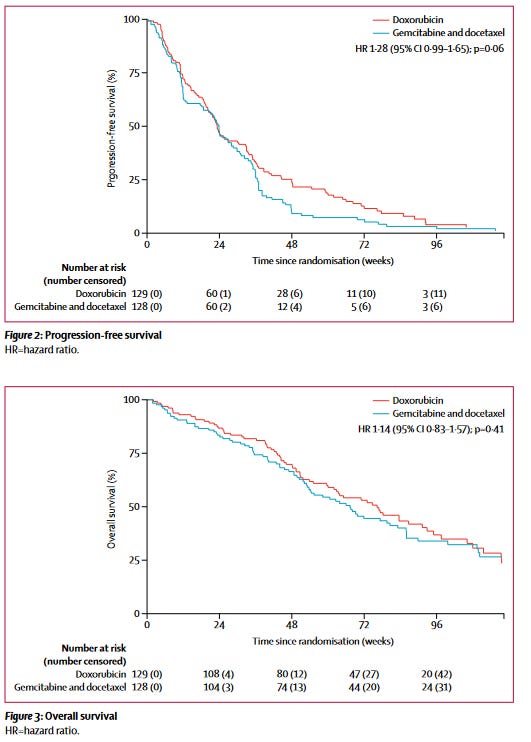

We thought, well, if not this combination, perhaps another might beat doxorubicin at its own game (this was done somewhat in parallel, really). This was the premise of the GeDDiS trial. 2 The GeDDiS trial likewise failed to improve over doxorubicin by its primary endpoint, progression free rate at 24 weeks. This is the equivalent of asking what proportion of patients did not have their cancer grow after 6 months. Keep in mind that being ‘progression’ in this instance includes a few things:

Growth of cancer by 20% in sum of diameters of target (read: chosen) lesions on imaging at any point, this can be after shrinking

Death

The proportion of patients with leiomyosarcoma was numerically higher in the GeDDiS trial, with a total of 47% of patients in the doxorubicin arm and 45% of patients in the gemcitabine and docetaxel arm having leiomyosarcoma (non-uterine and uterine combined). The figure included below, from the original manuscript linked in the above reference, shows the data nicely. There was neither a benefit in progression free survival, nor overall survival in this trial. The authors review some reasons why that could be the case, including dosage. More recent studies have looked, retrospectively, at alternative dosing of gemcitabine and docetaxel.3 The long and the short of this is that doxorubicin was not beaten within this population. It may bear revisiting to go through some of the finer points and I will in later posts.

Doxorubicin and Trabectedin

We have established that doxorubicin had not been toppled, through at least 2017. Where are we now?

We’ll spend the bulk of the following reviewing LMS-04, but the genesis of this trial was really LMS-02. LMS-02 demonstrated efficacy and feasibility of the combination of trabectedin and doxorubicin. 4 108 patients with metastatic leiomyosarcoma received 60mg/m2 intravenous doxorubicin followed by trabectedin 1.1mg/m2 on day 1 of a 3 week cycle, along with growth factor. The primary endpoint of LMS-02 was the proportion of patients who achieved disease control.

Disease control is a surrogate endpoint that includes:

Those patients with Stable Disease (less than 30% reduction in diameters AND less than 20% increase in diameters) at 12 week timepoint

Partial response (reduction in sum of largest diameters of target lesions by 30%)

Complete response (disappearance of target lesions on scans)

Patients were stratified into soft tissue and uterine leiomyosarcomas, which had a Simon’s two stage design. This in essence uses statistical mechanisms to test a question--rate of disease control--in the most efficient way. If you’re interested in Simon’s two stage modeling, see this reference for a nice calculator and paper. 5

The threshold of disease control was exceeded and was deemed to have a high enough likelihood that it should be tested in a randomized, controlled trial. This phase III trial was LMS-04.

Also worth mentioning, and while not part of the assessment, and again, not associated with survival in other randomized controlled trials, the response rate was numerically higher than had been shown in other trials—59.6% in patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma. See a plot of maximum change here.

The LMS-04 Trial

The LMS-04 trial is a randomized multicenter trial conducted by the French Sarcoma Group out of 20 centers in France.6 The treatment regimens were:

Doxorubicin 75mg/m2 once every 3 weeks for 6 cycles (normal dosing)

Doxorubicin 60mg/m2 AND Trabectedin 1.1mg/m2 every 3 weeks, followed by Trabectedin maintenance for 12 months (each is slightly reduced to account for cumulative toxicity).

Important to note that one of the arms continues chemotherapy until time of progression, while another has to stop by design. This is the standard, albeit that this Phase II study indicates you may be able to safely continue doxorubicin with dexrazoxane.7 It was published after LMS-04 started accruing.

The primary endpoint being evaluated was progression free survival (see definition per above). In total, 150 patients who were treatment naive were enrolled in the intention-to-treat population. They were randomized 1:1 to the two treatment arms above in an unblinded fashion. Patients were followed for a median of 36.9 months.

The headline is that they saw as a significant benefit in progression free survival at 12.2 months for trabectedin and doxorubicin vs. 6.2 months for doxorubicin alone. We are still waiting for the survival data. We know that trabectedin alone is already given to patients in the later line setting with improvement in progression free survival. Is this augmented by giving both in combination, or are we merely adding toxicity and not days of life?

There are some confounders here, to be certain. Patients were allowed to have surgery after the 6 cycles, and, having known that the response rate was higher, it would be anticipated that this is more likely to occur in the combination arm. There was a higher rate of surgery in the combination arm. Surgery would improve time to progression if it were performed on target lesions and could skew the results of the trial. Nonetheless, insofar as it might have been offered to either arm, this has in a way been controlled for—it’s simply important to note that some of the benefit to the primary endpoint is not purely from chemotherapy. Surgery will accentuate any benefit from a progression standpoint granted to the combination. Best response was determined by data prior to week 18, after which point a surgery might have been considered, but it was not the primary endpoint.

Ultimately, us physicians who treat patients with sarcoma await those final survival data. Nonetheless, the response rate, as well as time free of progression show a high level of activity, which has not been measured so clearly before. It does not appear based on available data that there is a plateau to the curves, which might sometimes indicate a fraction of patients are cured.

Given this is two different agents being given, each with known side effects, there is a higher rate of a need for dose reduction in the combined arm at 42% of patients for doxorubicin/trabectedin arm compared with 18 patients in the doxorubicin arm. Patients and providers will need to decide if that’s worthwhile.

Evaluating Table 2, in essence all Grade 3/4 adverse event rates were greatly increased for patients who got both doxorubicin and trabectedin. Interestingly, there was no increased rate of heart failure with the combination, although echocardiogram is part of monitoring each. Long term follow-up of patients may be important to better understand how it could affect heart failure risk years into the future.

The authors make appropriately reserved conclusions from their study, indicating that the combination can be considered for patients who need a high rate of response, or may feasibly undergo a surgery.

My Thoughts

I tend to agree with the authors that doxorubicin and trabectedin should be considered for select patients who require a robust response. Outside of that setting, I await the survival data, as it will need to be shown that patients who get doxorubicin with trabectedin concurrently live longer than those who get it in sequence. Famous papers for other types of cancer have answered this question in the past, with sobering results. 8 We should learn from our history in oncology, while also looking to the future as more novel agents are being discovered and tested for patients with leiomyosarcoma. 9

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045(14)70063-4/fulltext

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5622179

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33924080/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8446791/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35835135/

https://aacrjournals.org/clincancerres/article/27/14/3854/671519/Interim-Analysis-of-the-Phase-II-Study

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12586793/

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03425279