Chemoimmunotherapy for Sarcoma

Doxorubicin and Pembrolizumab

Obligatory—This is not medical advice

Doxorubicin remains the preferred first line treatment for most patients with a diagnosis of soft tissue sarcoma. This has been established over decades of Phase III studies, usually incorporating many sarcoma subtypes. Ultimately, no survival benefit has been shown to combinations for most patients, and, as a consequence, doxorubicin is preferred. We continue to try to find more effective treatments for our patients. In other types of cancers, such as lung or cancer of the biliary tract, adding immunotherapy has shown to improve outcomes. Within sarcoma, unfortunately, early phase studies failed to show a difference. Let’s talk about one of them here.

Types of Treatment

First, let’s reacquaint ourselves with the three groups of treatment. There is some overlap between each, so keep that in mind.

Cytotoxic: medications that kill cancer cells by breaking DNA, or inhibiting proteins needed for cell division or other processes in replication.

Targeted: medications that inhibit kinases, receptors, or hit targets in cells. This is a growing and very broad category that might incorporate antibody-drug conjugates (trastuzumab-deruxtecan) and TKIs (pazopanib).

Immunotherapy: medications that activate the immune system (eg pembrolizumab).

In prior posts I have reviewed some of the targets of immunotherapy and how they can harness T-cells to see and destroy cancer.

Understandably, there has been interest in how one might able to combine these forms of therapy for patients with cancer. As alluded to, prior trials in other forms of cancer have shown increased survival.1 There was a hope that this might be true for patients with sarcoma, as well.

Doxorubicin and Pembrolizumab

The study discussed here was a Phase I/II non-randomized, open-label single arm study of pembrolizumab combined with doxorubicin for patients with advanced (eg unresectable) sarcoma.2 The primary endpoint of the Phase II study was response rate. Here is a diagram of the design. Doxorubicin was capped at 6 doses, which continues to be normal for most sarcoma medical oncologists.

The phase I portion evaluated the combination of doxorubicin with pembrolizumab at two dose levels of doxorubicin, 45mg/m2 and 75mg/m2 combined with pembrolizumab 200mg every 3 weeks. Patients received 45mg/m2 in conjunction with pembrolizumab for two cycles. This was well tolerated, and so the dose was escalated to 75mg/m2.

As a result, the trial advanced to phase 2. The phase 2 incorporated SWOG 2-stage design.34 This assumed a null hypothesis of 15% for response to single agent doxorubicin and sought to detect a response rate of 35% for the combination. To minimize chance of futility, if fewer than 2 responses were seen in the first 20 patients, the trial would be halted.

In total, 37 patients were treated. Demographics were like what has been seen in other clinical trials for patients with a broad spectrum of soft tissue sarcomas. The most common histology was leiomyosarcoma. Regarding adverse events, they primarily were restricted to those previously seen with doxorubicin (see Table 2 below). Although preceding CTCAE, these AEs have been well described since the 1970s.5

Otherwise, there was a reasonable incidence of hypothyroidism (7 patients) and one case of adrenal insufficiency attributable to pembrolizumab. Some AEs cannot be so easily disentangled, as diarrhea may feasibly come from either agent.

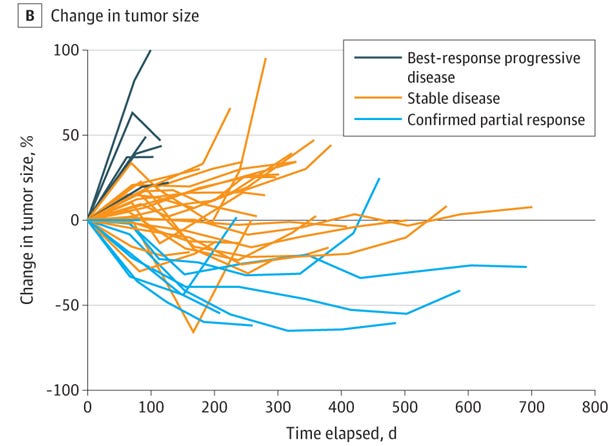

In total, there were 7 responses (19%), which did not meet the primary endpoint for the study design. As a result, it was not recommended that this combination proceed to phase III.

Some correlative analyses were also performed. Unlike with other types of cancers, PD-L1 expression was not associated with progression free survival or overall survival for patients in this group. No gene alterations were associated with progression free survival.

Interpretation

The combination of doxorubicin and pembrolizumab did not meet the efficacy threshold. Attempts at correlative analyses here have likewise not demonstrated a utility for PD-L1 in a broad population of patients with sarcoma. Some subgroups might be worth investigating individually. For instance, 2 of 3 patients with pleomorphic sarcoma and 2 of 4 patients with dedifferentiated liposarcoma had partial responses. Hopefully, future clinical trials will hone in on more narrow populations and be able to answer this question more definitively for our patients.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmoa1801005

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2770032

https://cancer.unc.edu/biostatistics/program/ivanova/SimonsTwoStageDesign.aspx

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19466315.2020.1865194

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/1097-0142(1971)28:4%3C844::AID-CNCR2820280407%3E3.0.CO%3B2-9