Angiosarcoma

Summary of Diagnosis and Treatment

Obligatory—This is not medical advice

We often discuss how it can sometimes take months from the first symptom to diagnosis of a sarcoma.1 This may be due to multiple factors. In the case of Bone bsarcomas, for instance, a younger patient may think that they simply have extremity pain from prolonged recovery from an injury. Cutaneous angiosarcoma might first appear as subtle skin lesions. For angiosarcoma involving other parts of the body, radiologic findings could look like benign vascular formations.2 Even under the microscope, lower grade angiosarcomas may be difficult to distinguish from non-malignant entities. Furthermore, the spectrum of behavior of angiosarcomas can also be highly varied. Adding to the difficulty is that angiosarcoma is an ultra-rare sarcoma with an age-adjusted incidence of 1 per 1M annually.3 It represents, altogether, only 2% of soft tissue sarcomas. There are well described predisposing factors for angiosarcoma (see figure). Treatment, of course, is varied, but let’s delve into the details more below.

Epidemiology and Diagnosis

In a review of the SEER database from 1973 to 2014, records of 4537 patients with angiosarcoma (AS) were interrogated. 4 Median age was 69 years, 54% of patients were female, and the most common site was the head and neck (26.29%). Most patients had been diagnosed between the years of 2005 and 2014, indicating perhaps increased awareness over the decades or increase utilization of adjuvant radiation. Although thought provoking, these data remain observational.

From a pathologic perspective, angiosarcoma expresses many of the same markers as blood vessels (endothelial cells), which includes CD31, CD34, ERG, amongst others. Epithelioid angiosarcoma can even stain positive for cytokeratin. To distinguish AS from Kaposi Sarcoma, AS is negative for human herpes virus 8. MYC amplification can sometimes be helpful, particularly in the setting of prior irradiation or lymphedema associated angiosarcoma. Normal grading systems are not usually used to describe angiosarcoma as that often belies biologic behavior.

Workup following diagnosis should include imaging, as well as consideration of MRI of the brain with and without contrast to rule out intracranial metastases. Attention should be given to lymph node basins, as AS is one of the few sarcomas that may have lymphatic spread.5

Treatment

For patients with localized disease, surgery with negative margins offers the best chance of cure for patients with AS.6 Utilization of radiation in such a setting has shown evidence of reduced rates of local recurrence, but long term survival data for this treatment are lacking. 7 That stated, data continue to accumulate and the field is far from settled. 8

For patients with advanced disease, anthracyclines as well as taxanes are the standard of care in most instances. 910 Individual providers might have particular preferences, but there has been a distinct lack of prospective data. Retrospective analyses appear to have similar efficacy, but these are far from perfect.

The most frequently cited first line agent is likely paclitaxel. This is based on a phase 2 trial that was published in 2008 called ANGIOTAX.11 Patients with advanced angiosarcoma were recruited at 9 French cancer centers. The primary end point was non-progression rate after two cycles of paclitaxel administered at 80mg/m2 every week for 3 of 4 weeks (eg days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28 day cycle) as assessed by RECIST.12 In total, 30 patients were recruited, of which 11 had received prior chemotherapy. Interestingly, during recruitment, the endpoint was changed to non-progression from response rate.

Side effects were like those previously seen for paclitaxel. Dose reduction and treatment delays were needed for 3 and 5 patients, respectively. The relative dose-intensity was 89% which, although this is an extrapolation, indicates the regimen was well tolerated.

This study, flawed though it might be, nonetheless, has established a degree of safety and possible efficacy of paclitaxel for patients with AS in the early lines of therapy.

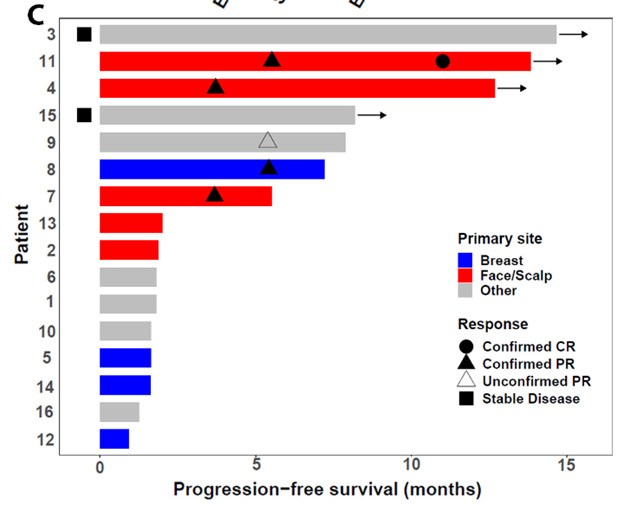

Data for treatment in later lines are somewhat mixed. Anecdotally, I would remark that there has been an increasing prevalence of administration of immunotherapy and this is likely secondary to data from SWOG S1609, cohort 51 as well as other, non-AS specific trials.13 SWOG S1609 cohort 51 was a small multicenter phase II with 16 patients within the DART trial.

Most patients recruited here had cutaneous angiosarcoma. The response rate was 25% overall. 75% of patients, however, experienced at least one adverse event, and 25% had a severe adverse event. Those reported included high grade diarrhea, infections, and elevated liver enzymes. We commonly see these with immunotherapy and they can be readily treated with immunosuppression.

As an aside, I would say that immunotherapy is often sold to patients as a formulation of medications that has few side effects. I would hope that as providers we can be honest with patients, as, generally, there has been an incidence of approximately 20% for SEVERE adverse events in combined checkpoint inhibition.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors have also been trialed in patients with AS. In a phase II, single arm study, 23 patients were evaluable for efficacy. Amongst those, 17.4% had a response with a median progression free survival of 5.5 months.14 My conflict of interest here is that I was co-first author of the manuscript. These results are thought provoking and may indicate a role for regorafenib, or other TKIs, in future trials for patients with AS.

Although individual phase II studies may produce adequate signal to move on to phase III, the best steps to help our patients is creation of platform to test multiple hypotheses concurrently. Such systems have been implemented for patients with breast pancreatic, and other cancers.1516

This is not to say that important work isn’t being done! Take, for instance, the Angiosarcoma Project, which has shown light on the genetic underpinnings of AS.1718

Interested patients should consider visiting the project’s website: here.

Conclusions

Angiosarcoma is a rare cancer which develops from the lining of blood vessels. Altogether it represents approximately 2% of soft tissue sarcomas. The diagnosis of angiosarcoma can often be complicated and may require expert evaluation. Local disease should be approached with curative intention surgery and/or radiotherapy. Treatment for most patients with advanced angiosarcoma involves initiation of cytotoxic chemotherapy often followed by immunotherapy. Despite early phase trials, the most appropriate sequence of treatments remains unknown. Studies evaluating the pathogenesis of angiosarcoma, as well as the efficacy of other forms of treatment are ongoing. That stated, we continue to lack phase III data that might more specifically inform practice.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7046415/

https://radiopaedia.org/articles/musculoskeletal-angiosarcoma?lang=us

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29220293/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31612920/

https://www.nccn.org/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20537949/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8635113/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34359716/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18809609/

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cncr.26599

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18809609/

https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/docs/recist_guideline.pdf

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34284255/

https://www.ispytrials.org/

https://pancan.org/research/precision-promise/

https://ascproject.org

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32042194/